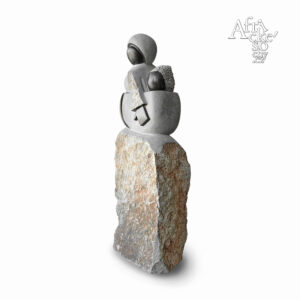

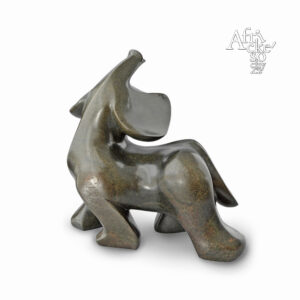

Sculptures for the house and the garden

In the on-line gallery AfrickeSochy.cz, you may choose and buy sculptures from natural stone for your living room or your garden. Stone sculptures made by sculptors in Zimbabwe are imported to the Czech Republic by Ateliér AfrickéSochy.cz.

All details about sculptures, sculptors and stone you can find below on this page. Click on an image in the on-line gallery to see price, size (rozměry), and weight (hmotnost) of a sculpture. Contact us if you wish to buy a clupture.

New sculptures in the e-Gallery

Check out the new sculptures added to the e-Gallery

Sculptures in the arrangement of the apartment

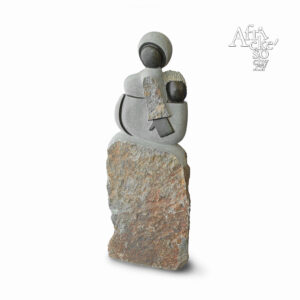

Enhance your interior for an extra dimension. Besides paintings and graphics the sculptures fill your interior with a third dimension – depth. Statues are a fusion of light and substance. They are changing during the day and the night as the light changes, light which helps to create them. Again and again discover new faces of your statue. It is an experience worth trying.

Do you want to be advised on how to best place the sculpture in your apartment or house? Interior architects and designers whom we work with are ready to assist you.

Decorative additions play a very significant role in the design of any garden

Situate a new dominant element in your garden. While your garden will change during the year and turn in green and bloom colors, sculpture in your garden will be dignified dominant arrogant to transience changes of the year cycle. Just as jewelry is eye-catching detail that adorns a woman, so will sculpture adorn your garden. Statues will be your partners sitting with you in the garden. They will be the focal point again and again attracting your attention or that of your guests.

Choose a sculpture from the wide range of sculptures in our e-Gallery

Are you trying to ensure that your garden is a harmonic background of your home? Read more about Feng Shui.

Why buy sculpture?

Sculptures bring satisfaction to our desire for beauty, a desire to experience positive emotions, a desire to find harmony and to feel happy. Sculptures create an atmosphere or may be a memory.

A living space that is missing the beauty of art, is one in which the soul is missing.

Time and again sculpture will attract you by its beauty; you will be enhanced; it will inspire you and enable you to forget your everyday worries.

Sculptures of African sculptors, more than any other contemporary art, carry inside them the atmosphere of the landscape in which they were born, and the pulse of life of their authors. They carry within themselves the story. Black color stone radiates the heat of African nights and in silence you can hear rumbling drums line and people singing monotonous tunes. Just only touch the statues themselves and you feel it all.

We aim to introduce you to the beauty of art, to give you joy, and other positive emotions. Our goal is to make the art an inspiration in your everyday life.

How to place the sculpture in the interior

Some of the sculptures were carved by sculptors in Zimbabwe, so that they have a center of gravity too high above the base of the statue, and they are not therefore sufficiently stable just by placing them on furniture, shelf or directly on the floor. The risk of accidentally dropping sculptures increases in households with small children or pets. We therefore deliver sculptures weighing less than 50 kg on a square or rectangular base made of oak or beech boards. This kind of base provides sculpture with sufficient stability against accidental fall. Heavier sculptures typically require individual installation and fixation.

The base is fixed to the sculptures by a screw. The base can always be removed and replaced with another base or the statue can later be installed in a permanent manner, such as by sticking. The surface of the wooden base is treated with colorless or dark brown wax on wood. This wax finish is not suitable for wet environments, such as a bathroom.

Zimbabwean sculptors are usually carved so that they are intended to be viewed from all angles. By placing sculptors close to a wall or in a corner, they can lose some of their „faces“. If your interior allows, it is suitable to place a sculpture on a pedestal, base, or a little table standing freely in a space. Such placing of sculptures was common in the interiors before the Second World War or even in older interiors. Even today, you can find very nice pedestals or small tables in antique shops. An antique pedestal and a piece of modern sculpture can create in the interior an impressive solitaire.

A modern pedestal and replicas of old ones is of course possible to order. It all depends on your taste and on your decision of what area you make available for the sculpture in your interior.

How to place the sculpture in the interior

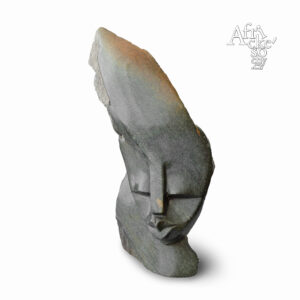

The color of the finely worked or polished serpentine is light gray. Areas that are dark, rich in color and gloss, are treated with wax. Sculptors warmed sculptures directly by the open fire before waxing them. The surface of most sculptures is porous and deep wax soaks to hot stone. Sculptors polish-over then the cooled wax with a clean cloth to achieve a high gloss.

Statues in the interior

Statues in the interiors do not require any special care. Dust is best wiped with a soft cloth or duster. Be careful, a polished surface can be scratched sometimes even with a ring.

Sculptures in the gardens

Not all sculpture is in a European climate suitable for placing in the garden during the frost period of time. Especially brown serpentine can absorb moisture that may freeze in winter and it can disrupt the sculpture. Also if moisture frosts in any cracks of the stone, it can damage the sculpture. Before the frost period it is therefore appropriate to protect sculptures in the gardens with, for example, shrink-wrapping.

Wax exposed to rain gets dull after some period or it can wash away completely after a long period. Approximately once every two years it is therefore appropriate to renew the wax and to polish the surface of the sculptures in places where the luster has been lost.

Stone sculptures and Feng Shui

Chinese art is built on a completely different view of the world from how it is approached by Western science. So it is not easy for Europeans to take in these different perspectives and to identify with them. Awareness of Chinese art and people who practice them, are gradually growing in the traditionally less spiritually based Western world. Feng Shui is the art used in China for several thousand years. Its aim is to harmonize the flow of energy in areas in which we live, and thus improve the atmosphere of a home, of relationships with others, to achieve greater inner satisfaction, wealth and to gain new energy to realize our wishes and dreams.

A key area of feng shui is to achieve a balance of the opposing forces of yin and yang. Yin represents the feminine, passive, negative principle. Yin is earth, darkness, moon and death. Yang is the male principle, positive. Jang is heaven, light, sun and life. The world is in the Eastern concept the unity of these two principles; one cannot exist without the other, as evident from tajchi symbol. Two principles together form one unit and one is always contained in the other.

Items in our interiors and gardens create and represent one or the other of two energy principles. The correct placement of objects representing the five elements (fire, water, wood, metal, earth) in eight areas of effort (for example, career, health, family, wealth and prosperity, marriage and relationships) can be achieved by harmonizing the flow of chi energy and the desired balance, harmony, contentment, and happiness can be so achieved.

Stone sculptures represent the positive energy yang and it is possible to achieve proper balance and flow of energy by their appropriate location in the interior or garden. Experts in feng shui can change the placement of your furniture, use of colors and placement of statues and decorations in your home to help you in improving the overall quality of your life and personal happiness.

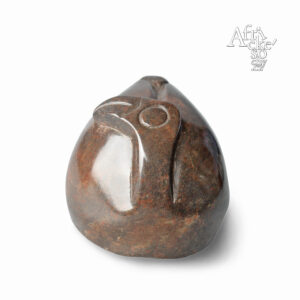

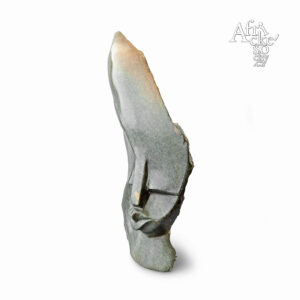

Stone for sculptures

The stone that sculptors use most often is serpentine. It covers a range of colors from olive green to shades of brown to black. The color at the edges of stone often turns into a brown or reddish-brown color, and sculptors know how these transitions of colors masterly use and incorporate them into their sculptures.

The stone used for statues is mined by hand in the quarries in Zimbabwe. The use of explosives could disrupt the internal structure of stone sculptures and cause cracking during processing.

The rough shape of sculpture is reached by using a chisel and hammer; then the softer contours are made by a special hammer for sculpting (a hammer has a blade with three or five points). The surface of sculptures is smoothed firstly with rasp, then with the finer rasp and finally honed by wet sandpaper. The finished sculptures are heated by an open fire and the whole sculpture or only selected areas are infused with wax. Wax is literally soaked in warm stone; the originally gray color of stone darkens and fine structures in stone, metal veins and spots in different colors can be nicely seen.

The history of modern Zimbabwean sculpture

The beginnings of sculpture in Rhodesia (1950‘s and 1960‘s)

In former Rhodesia, sculpture developed from the tradition of African handicrafts. The most commonly used materials were wood, china clay, and wild grass. Objects such as stools, bolsters, and walking sticks were often decorated with animal or with anthropomorphic motifs and offered room for the artistic talents of craftsmen. The same applies to carved masks and statues used for ritual purposes. Modeling from clay in order to produce ceramics, or just as a pastime, also has a long tradition in Africa.

The first people to begin encouraging artistic activities among the indigenous black population were Christian missionaries. In 1940, a priest Canon Edward Paterson set up a primary school for black boys within the Cyrene mission. Pupils of the school gained a general education and some knowledge in agriculture and house building, as well as skills in woodcarving, drawing, painting and later in sculpture. Canon Paterson left the mission in 1953, but he continued teaching art until his death in 1974. Father Hans (John) Groeber founded a mission in Serima in 1948 in which he taught mainly woodcarving and drawing in the 1950’s and 1960’s.

The main incentive for the development of modern art in Rhodesia was the foundation of Rhodes’s National Gallery in the capital city of Salisbury (Harare) in 1957. The first nominated director of Rhodes’s National Gallery was Frank McEwen, an English artist and art expert. The gallery was established in order to collect and exhibit works of western artists, and not to promote local Rhodesian art. However, McEwen soon recognised the artistic potential of Rhodesians whom he was meeting. So, he began to encourage and aid talented black artists in their own artistic production and he set up an unofficial art workshop with the gallery. At first, McEwen tried to encourage traditional African techniques of working with wood and straw, and to teach artists the basics of painting. However, the focus of the workshop changed following a meeting between McEwen and an amateur sculptor, Joram Mariga. Mariga brought stone sculptures, which he had created from soapstone, to the meeting. McEwen immediately understood the potential combination of working with the stone and the skills of the Rhodesians, so he focused the workshop on stone sculpture. Joseph Ndandarika, Boira Mteki and Thomas Mukarobgwa were among the first artists trained in the workshop.

Encouragement and financial support, which Joram Mariga was receiving from McEwen, enabled him to set up a small group of sculptors in the Nyanga Mountains, not far from the border with Mozambique. It was within this group that sculptors such as Crispen Chakanyuka, the brothers Bernard and John Takawira received their training.

In 1962 the works of Rhodesian painters and sculptors were first exhibited, and a tradition of regular exhibitions organised by the National Gallery began. A favorable reaction to these exhibitions enabled McEwan to establish an official art school (the Workshop School) with the National Gallery, and it was this institution that helped educate dozens of sculptors and painters in the following years.

In the spring of 1965 the Rhodesian government, under Ian Smith, proclaimed the independence of Rhodesia from Great Britain. Yet, other countries refused to recognise this and the UN imposed sanctions on Rhodesia. These, among other restrictions, prevented the country from exporting agricultural products. One of the farmers afflicted by this situation was Tom Blomefield. As a result of the loss of tobacco sales a lot of workers on his farm lost their jobs. Tom Blomefield decided to start creating statues alongside his workers in order to find a new way of earning a living both for himself and for his employees. Another favorable circumstance securing the future community of sculptors was the fact there were sources of high-quality stone for sculpting available near the farm. People from nearby farms and villages soon heard about the emerging community and started to come and try working with stone. Those who discovered an artistic talent within themselves began to settle down in this place, later named Tengenenge. When Tom Blomefield brought some of the first statues to the National Gallery, McEwen was excited and took Tengenenge under his protection.

In 1966 statues by sculptures from Tengenenge were first exhibited at the annual exhibition organised by the National Gallery and in the following years they continued in winning recognition. This period of Tengenenge is associated with artists such as Enos Gunja, Ephraim Chaurika, Sanwell Chirume, Edward Chiwawa, Bernard Matemera, Leman Moses, Sylvester Mubayi and Henry Munyaradzi.

The way to galleries around the world (the late 1960’s and early 1970’s)

McEwen tried to establish the new Rhodesian sculpture in the world as a fully-fledged movement of modern art. There were dozens of exhibitions in the USA (including the Museum of Modern Art in New York) and in South Africa in the years 1968 and 1969. In 1970 McEwen succeeded in organising an exhibition of the statues in the Museum of Modern Art in Paris (Musee d“arte Modeme de la Ville Paris – Art Faricanie Contemporain de la Communaute de Vukutu) and a year later he repeated the success, this time in Paris’s Rodin Museum (Sculpture Contemporaine des Shonas d‘ Afrique). Other important exhibitions took place in the I.C.A. Gallery in London and in the Museum of Modern Art in New York, both in 1972. After these successful exhibitions Zimbabwean sculpture became a fully recognised movement of worldwide modern art.

Before 1969, the works from Tengenenge were exhibited (and sold) in exhibitions in the National Gallery and various other galleries in the world together with the works of artists from the National Gallery and from Nyanga, a third center in which the art of sculpture began to develop in Rhodesia. However, in 1969 Tom Blomefield decided to organise the exhibiting, exporting and selling of statues directly from Tengenenge, and not through the National Gallery, which led to a break up with McEwen and with the National Gallery. McEwen was focusing on the high artistic quality of the exhibited statues (though the only criterion being his own opinion), whereas Blomefield gave the sculptors a free hand in trying to gain recognition and to succeed commercially.

Shona art

Negative feelings from the world public towards the new Rhodesian establishment (and also towards art calling itself Rhodesian) in the early 1970‘s, a break-up with Tengenenge (which led to the need to differentiate sculptures coming from other centres in Rhodesia) and possibly also an effort to make the new Rhodesian art mysterious led McEwen to adopt a new strategy for the promotion of the statues – that is creating the term ‘Shona art‘. The Shona are the majority ethnic group in Zimbabwe (80%) and although not all artists in Zimbabwe are Shona, this term has been used to refer to modern Zimbabwean art ever since.

Civil war (late 1970’s)

Political tensions between the black majority and the white minority were escalating from the beginning of the 1970’s. Guerrilla groups were coming into the country from Mozambique and Angola trying to overthrow the minority white government. In 1973 the political atmosphere led McEwen to resign from the position of the director of the National Gallery. His support of black art was no longer acceptable to the trustees of the institution.

When he left the National Gallery, the Gallery artistic workshop began to decline and the main centre of sculpture in Rhodesia moved to Tengenenge. However, this period did not last long. The guerrilla war against the white government intensified in the mid 1970’s, and both cities and the country ceased being safe. People practically stopped creating and selling works of art.

Independent Zimbabwe (1980’s)

Sculpture started to develop again after 1980 when the white minority lost power in the country and the independent Republic of Zimbabwe was established. The long guerrilla war ended and the economic sanctions were called off. Once again Tengenenge became the centre of Zimbabwean sculpture. However, some artists such as Fanizani Akuda, Sylvester Mubayi or Henry Munyaradzi, who had left Tengenenge at the end of the 1970’s, did not return but decided to set up their own studios. However, the open society of sculptors in Tengenenge offered the space to other talented sculptors and a new generation of sculptors was established. This generation is represented, for example, by David Bangura, Davison Chakawa, Wonder Luke, Alice Musarara and Endronce Rukodzi. Furthermore, the artistic workshop was reopened with the National Gallery (renamed to the National Gallery of Zimbabwe) and the Gallery continued in the tradition of regular art exhibitions (renamed as the Zimbabwe Heritage in the mid 1980’s). An American Roy Guthrie became the only promoter of Rhodesian art abroad after McEwen left the National Gallery. Guthrie began organising exhibitions of successful sculptors in different countries, and in 1985 he founded the Chapungu Sculpture Gallery – a large sculpture park with a gallery and a studio on the outskirts of Harare. The artistic and commercial success of sculptors from Tengenenge, or those exhibiting their works at the Chapungu Sculpture Gallery, inspired other artists to set up small studios all around the country.

Years of prosperity (1990’s)

In the 1990’s sculpture in Zimbabwe flourished. The relative economic prosperity of the country fuelled sales of sculptures, both in Zimbabwe and abroad. An open-air exhibition was organised in Wageningen, in the Netherlands in 1989 and its success enabled Tom Blomefield and the sculptors from Tengenenge to introduce and sell their works at dozens of exhibitions in Western Europe, especially in Germany and the Netherlands. In the 1990’s sculptures from Zimbabwe also began to be sold in a number of small galleries around the world and with the emerging Internet, the galleries of Zimbabwean/Shona art spread to web pages as well.

Sculpture in the times of economic and political crisis (21st century)

Since the late 1990’s, and especially due to a land reform carried out in the year 2000, Zimbabwe has been struggling with a deep economic crisis. Hyperinflation completely disrupted the economy – Zimbabwe practically abandoned its currency and adopted the American dollar. It was mostly the larger sculpture studios that asserted themselves in the difficult situation of the first decade of the 21st century, some of the foremost being the studio of the sculptor Dominic Benhura, or the association Friends Forever, founded by Mike Munyaradzi. In December 2007 Dominic Benhura took over the sculpture settlement in Tengenenge from Tom Blomefield, who due to his age had failed to provide it with strong leadership in several previous years. Thanks to this change there is some hope that the forty-year tradition of the sculpture community, as well as modern Zimbabwean sculpture itself, will continue.

Tengenenge

Tengenenge is a typical African village. What makes it different from thousands of other villages scattered throughout southern Africa is the occupation of its inhabitants. In Tengenenge live almost exclusively sculptors and their families. They began to settle there from the mid-60s of the last century at the instigation of a white farmer, prospector and bohemian Tom Blomefield. Today, nearly two hundred sculptors live there. Most of the sculptors live with their families directly in the Tengenenge. Some sculptors live in the surrounding villages and attend Tengenenge to work on sculpture.

Each of the sculptors has dedicated space where he/she exhibits sculptures. Tengenenge is the largest open-air gallery of statues in the world. It is almost impossible to estimate the number of statues that can be seen in Tengenenge in one moment. What is certain is that there are thousands of statues.

The uniqueness of Tengenenge is also due to its natural wealth hidden in the hills of the Great Dyke, at the foot of which the village lies. The mountain range stretches at the length of several hundred kilometers from north to south through central Zimbabwe plateau and the mountains are rich in metal ores. Great Dyke offers residents of Tengenenge other resources – supplies high-quality stone suitable for sculptural work. Near the village are mined serpentine and spring stone – a harder dark black variety of serpentine.

The village wakes up with dawn and falls asleep with the sunset. The economic crisis in Zimbabwe drove electricity prices to sums that the village cannot afford to pay these days. So life in Tengenenge returned to the rhythm of life, which was natural for people for thousands of years, to the rhythm which is limited by the morning sun and evening alpenglow.

As soon as the sun rises in the morning the beating of stone hammers begins to sound though the village and it does not quiet down until the evening twilight. The background sound of sculpting is just another fragment in the mosaic consisting in an unrepeatable genius loci of Tengenenge. It is due to the position of the village in the foothills of the Great Dyke, due to thousands and thousands of statues scattered under the trees around the village and ubiquitous tapping of sculptor’s chisels. All this creates an atmosphere that once you visit the village immediately conquers your heart.

Charitable projects in Tengenenge

Whoever asked the question of whether or how we can help people in Africa knows that finding the answer is not simple. The only effective help is, in our opinion, the one that supports their own activity and the emancipation of people to whom the aid is directed. That is why we support the sculptors in the community of Tengenenge or in studios in Harare by purchasing the sculptures directly from them. There are no more traders on the way between the sculptor and the final owner of the statue.

But we are aware that if children in Africa learn to read and write it greatly increases their chances of applying for and obtaining better-paid work. Therefore we welcomed the activity of Marie Imbrova. She is an ethnologist and a former diplomat in Zimbabwe, who initiated the establishment of the association Klub přátel Tengenenge in 2010. Klub is a civic association which aim is to support children in the sculptor’s community Tengenenge so they can attend school and get a basic education. In favor of the Klub we organize various events to raise funds for the activities of the Klub.

Contacts

Here you will find our show room

GPS coordinates: N 49° 58.30745′, E 14° 41.16912′

Showroom of Ateliér AfrickéSochy.cz in Tehov has no fixed opening hours. The visit is possible after prior arrangement. Contact us by e-mail or phone numbers below.

CONTACT FORM

Fields marked with (*) are mandatory and must be filled in.

Contacts

We will be happy to answer all your questions about sculptures and artistic items offered in our e-Gallery. Write us a message from the contact form or call us.

Ateliér AfrickéSochy.cz

- Art-n-coffee, spol. s r.o.

- Id. No.: 03583023

- VAT No.: CZ03583023

- Ing. Ondřej Homolka

- Id. No.: 63839334

- VAT No.: CZ6709141395

- Address:

- Císařova 274

- 251 01 Tehov

- o. Praha – východ

-

Ing. Ondřej Homolka

- + 420 777 935 970

-

PhDr. Hana Homolková

- + 420 777 124 329

zc.yhcosekcirfa@yhcos

www.africkesochy.cz

- GPS coordinates and map:

- N 49° 58.30745′, E 14° 41.16912′